Comics Alternative Re-Post: Denis Kitchen

/In 2014, I did a few interviews for the late, much missed podcast and comics news site Comics Alternative. I recently discovered no one took over the site after Derek Royal’s untimely death, but parts of it can still be found on the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine. I’m reposting them here so they will be easier to find.

Here’s an interview with Denis Kitchen from October 2014.

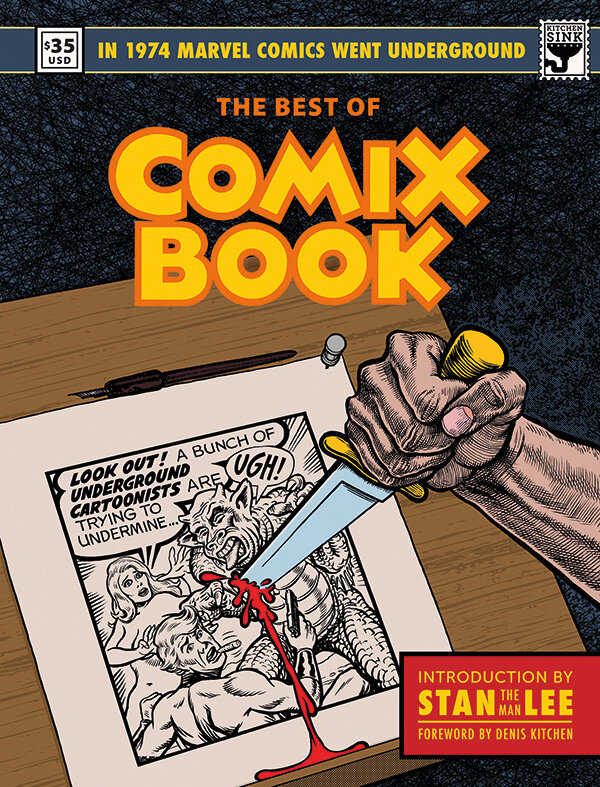

Kim Munson: Congrats on the Harvey Awards for Kitchen Sink’s The Best of Comix Book!

Denis Kitchen: Feels good, Kim! Especially after winning the two awards for our debut title. It also felt good to have that material finally be reprinted after literally 40 years. I also have to add how gracious and enthused Stan Lee was about this experimental material. He went way out on a limb back in 1974. I’m astonished what us hippie cartoonists got away with on Marvel’s dime!

KM: How does it feel to be a publisher again?

DK: The nice thing about the new imprint arrangement is that my Kitchen Sink Books partner John Lind and I get to focus completely on the editorial and design side of books, while our publishing partner Dark Horse gets to do the “fun” stuff like dealing with manufacturers, distribution, warehousing, collecting money, and certain other aspects of publishing we’re happy to be peripheral to!

KM: The Best of Comix Book has a great cover by Peter Poplalski, who also did the original 1973 cover for Comix Book #1, and this lovely portrait of you.. You’ve been at one comics convention after another, from San Diego Comic-Con International in July to the New York Comic Con that just wrapped up. What interesting trends have you spotted?

DK: Besides that everyone is getting younger and younger? Or than non-comics elements keep taking over the real estate at big conventions? There seems to finally be an actual gender balance. And I’ve noticed that many of the youngest comics creators are on Tumblr and other sites that bear only a passing resemblance to the printed matter still dearest to me. Hopefully, there’s room — and a market — for all formats. Most people still seem to like physical publications. We’re working the higher-end market, where there’s a certain fetishistic element to owning beautiful books.

KM: I heard that Kitchen Sink’s next book is a premium re-issue of Kurtman’s Jungle Book. Are you adding new material?

DK: Yes, definitely. John Lind redesigned the book, so it’s really sharp looking. And there’s considerable new material: I wrote an essay to put this important 1959 work in context. Then Gilbert Shelton, who first broke in with Kurtzman’s Help! magazine wrote an intro. We also have a dialogue between Robert Crumb and Pete Poplaski about Jungle Book. And we recycled Art Spiegelman’s intro from the late ’80s Kitchen Sink edition. So, basically, there are varying texts by five guys who all grew up worshipping Kurtzman. I know older Kurtzman fans will support this, but what we really want is to introduce Kurtzman to a newer generation of fans. Jungle Book is the first of a half dozen or so out-of-print or never-before-collected Kurtzman works on our publishing agenda.

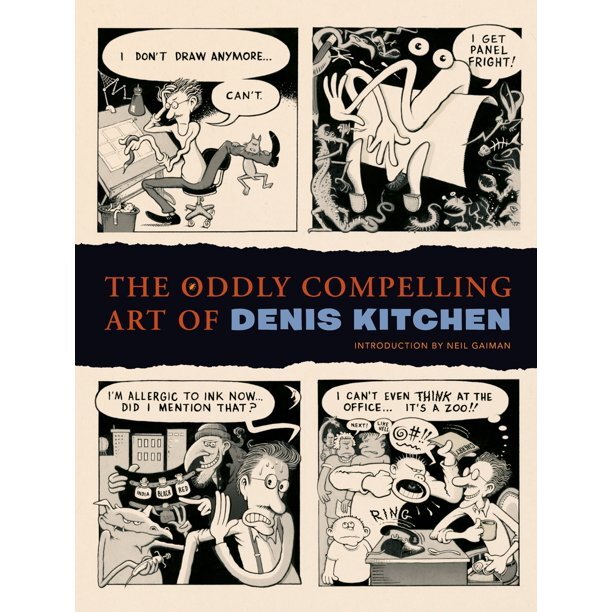

KM: Switching to your artist hat — you just opened an art exhibit of your own work at the University of Wisconsin, called The Oddly Compelling Art of Denis Kitchen, which is the same name as your Eisner Nominated 2010 book. That must have been gratifying since you grew up in that area. Tell me about the show and what that experience was like.

DK: It was especially gratifying to have an exhibit where I could meet old friends and family. The gallery asked me to provide a show predominantly of my own work, but also with examples of a few artists who had an influence on my career. So a little over half the exhibit was my art, with the rest comprised of originals by Will Eisner, Al Capp, and R. Crumb. I received top billing on the poster because I was the hometown boy, but it’ll be the last time I get billing over any of those artists again.

KM: I see you are featured on the cover of the Spring 2014 issue of TwoMorrow’s Comic Book Creator.

DK: Yeah, the cover where I did a self-portrait literally showing all the hats I wear? That’s a phrase I’ve used a lot to describe my career, but it was the first time I tried to actually show the hats. The artist me is of course wearing a fancy general’s hat, then, the CBLDF hat is a Viking helmet, et cetera. The agent hat — clearly my least favorite — looks like a Ku Klux Klan hood. Jon Cooke interviewed me at considerable length and the manuscript turned out so long — 75,000 words, I think — that they couldn’t fit it in the magazine, so the last half is posted online.

KM: Speaking of exhibitions, I see there’s currently an Eisner Show at OSU/Billy Ireland. I’m glad to see these shows of his work. It keeps his work alive and helps new people discover him.

DK: Indeed. The bulk of that exhibit comes from OSU’s own Eisner collection with a few gaps I filled in from the family’s archives I oversee here. Eisner is one of those seminal comics creators whose legacy continues to grow, which is very satisfying to see. Every year there are two or three Eisner exhibits here and abroad. There’s one in Munich next spring tied to The Spirit’s 75th anniversary, and conversations going on about possible others. And for the centennial of Will’s birth in 2017, at least two museums in Europe are planning a major traveling show.

KM: Masterful Marks is out from Simon & Shuster, and I remember you said that you were nervous about your contribution about Dr. Seuss. Are you ultimately happy with it? The book is beautiful.

DK: Thanks. I thought editor Monte Beauchamp did a masterful editing job on that. I recall being nervous when we spoke because he’s such an icon, but I’m very pleased with how my mini-graphic bio came out. There are always a couple of panels you wince at and want to fix, but I’m happy with it. I think I was chosen because I can easily ape Seuss’s style. The Huffington Post recently did a nice piece on my cartoon. That was an unexpected surprise because I was in such great company.

KM: Did anyone else’s contribution particularly impress or surprise you?

DK: I was particularly impressed with Drew Friedman’s take on Crumb. Drew’s art is always stunning, but I liked the way he worked in his personal relationship with Crumb, while also giving readers a sense of Crumb’s career, not an easy mix. I definitely enjoyed Peter Kuper’s job on Harvey Kurtzman, and I learned a lot about some artists I only knew on a kind of superficial level. The one I’m still scratching my head over is the Jack Kirby chapter by Mark Alan Stamaty, whose style is just so 180 degrees different than Kirby’s that I found myself visually disoriented. That one may yet grow on me. But it’s a great collection. I was thrilled to be a part of that ensemble.