Comics Alternative Re-Post: Steve Leialoha

/In 2014, I did a few interviews for the late, much missed podcast and comics news site Comics Alternative. I recently discovered no one took over the site after Derek Royal’s untimely death, but parts of it can still be found on the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine. I’m reposting them here so they will be easier to find.

Here’s an interview with Steve Leialoha from August 2014.

In June, I had the opportunity to visit with Steve Leialoha, veteran comics artist, about his career and future plans after his twelve-year involvement in Fables, which is wrapping up with issue #150. An all-around excellent artist, but best known as an inker, Steve has been working professionally in comics since the 1960s, starting with fanzines, then moving on to Marvel and DC. A native San Franciscan, he is tall and soft-spoken with an easy smile. His father was Hawaiian, infusing Steve with a love of Hawaiian culture and also an affection for quirky stereotypical interpretation of it (he particularly likes the Tiki Room at Disneyland-Anaheim). He travels to Hawaii frequently to visit his extended family.

We had a nice chat over sandwiches sitting on the back patio at Through Bread in San Francisco’s Market/Church Street neighborhood, and then adjourned across the street to the flat he shares with his partner, comics creator and “herstorian” Trina Robbins. We talked in their home office surrounded by memorabilia and Trina’s collection of Wonder Woman knickknacks. In a place of honor over the computer is a stunning splash page drawing of Wonder Woman fighting the Cheetah, by Harry G. Peter, drawn around 1948. Steve had bought this drawing for Trina at a convention about twenty-five years ago and said that it may have been originally intended for Comics Cavalcade, but it may not have been printed until the 1970s.

Kim Munson: Trina tells me this [Wonder Woman] page is the star of her collection.

Steve Leialoha: There’s very little original Wonder Woman art around. As far as I know, that’s the nicest splash page in existence.

KM: So, Steve, how did you start? Were you always drawing as a kid? Did you read comics?

SL: As a kid, I was always drawing. My dad would always give me comics. I mean, he would like to read all sorts of stuff, and he would pass everything along to me. Harvey comics and that kind of thing, when I was six or seven. As I got older, the Marvel Age, which I think of starting like in 1962, I was ten, which is certainly a good age for reading that stuff.

KM: It’s always interesting how people break into the industry. What’s your story?

SL: Oh my — the humble beginnings… In high school, during the days of fanzines, back in those pre-digital days when you couldn’t just email somebody and get information, we’d found out about fanzines and whatnot through magazines like Creepy and Eerie and Castle of Frankenstein. I started to get interested in seeing if I could get some of my drawings published. I wrote out a few inquiries here and there and got some early fanzines, and one was a thing put out called…I can’t even remember the title of it, but the editors were Marv Wolfman and Len Wein, two young guys who had not yet turned professional.

So, anyway, the first comic I ever attempted was written by Marv Wolfman and I drew it on ditto masters. That was back in 1967.

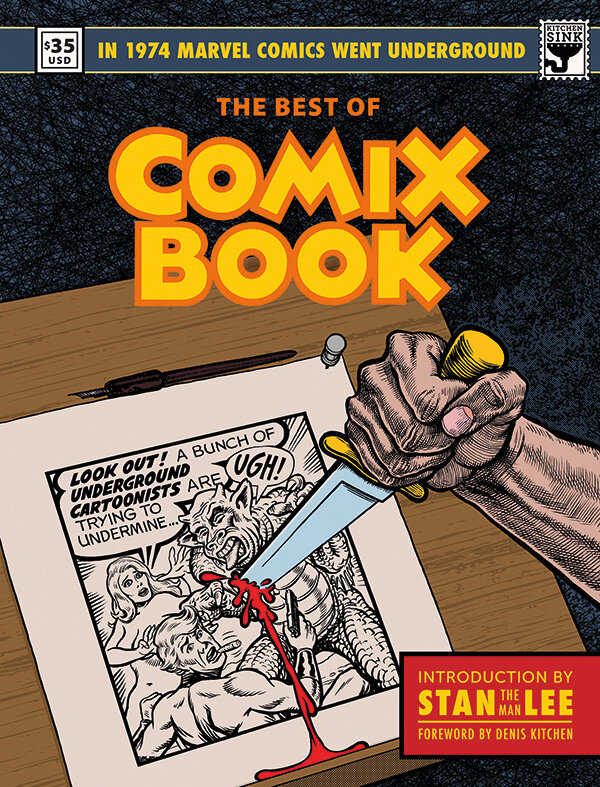

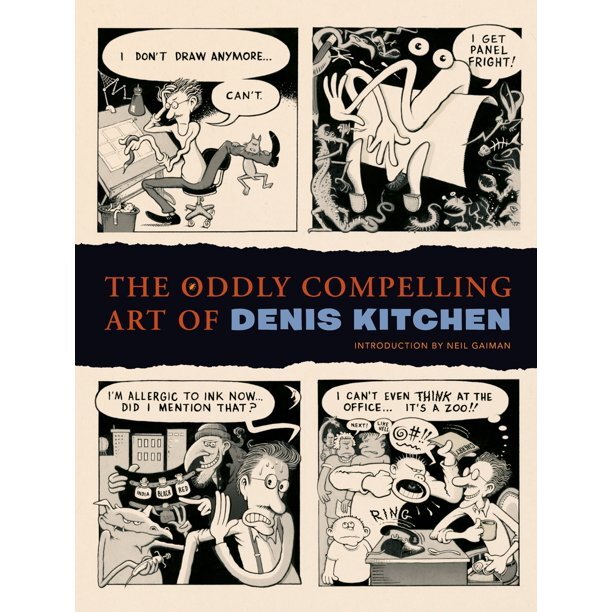

At San Diego Comic-Con around 1970, I met Mark Evanier. He encouraged me to draw one of his scripts, so my first published work was in a Dennis Kitchen comic called High Adventure, which came out in 1973. Mark wrote it and I drew it, and John Pound was the inker on it. In hindsight, it wasn’t so bad. I mean, it wasn’t the greatest thing in the world, but it was a nice way to start .I was always grateful to Dennis Kitchen for publishing me.

KM: How did you discover inking? Did you always draw in ink, or was that a new thing? How did you get into that?

SL: By the early ’70s I started going to conventions and was being inspired by getting to meet guys like Jack Kirby, and I remember having a nice chat with Burne Hogarth and all of these well-established icons of the comics world. Back in those days, the common wisdom was that you had to live in New York to work in comics. So I never really considered it, but as the ’70s progressed, they began to loosen up those rules, realizing that you could actually work by mail and it would be just fine.

In the early ’70s, a lot of the guys that worked for Marvel moved to Oakland and Berkeley, and I started showing my work to some of them. People like Mike Friedrich, who was actually from here [San Francisco] originally, Alan Weiss, Frank Brunner, Jim Starlin; they were living in Oakland at that time. Alan Weiss wanted to hire some local inkers to help him on various projects, so I started showing samples to him, and Jim Starlin saw some of them. He wanted to be able to pencil and ink a whole issue of Warlock before sending it in to the office.

KM: How did they usually do it?

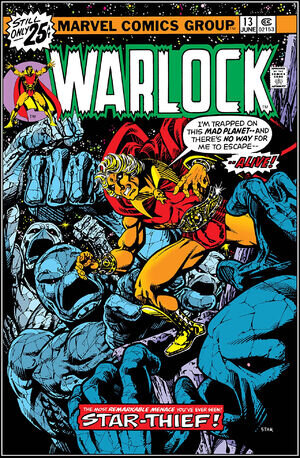

SL: The usual method was to pencil a book, send it into the office, they would check it, send it off to the letterer, then it would be sent off to the inker. Starlin wanted to have the whole thing done out here so that he could send in a complete book. It saved a lot of time. Tom Orzechowski, ace letterer, was also living out here. At that point in time, my drawing wasn’t that good. My inking was better than my penciling. So, why not ink? And working with Starlin was great for me as an inker because it just happened that my favorite book at that time was Warlock, and Jim was doing extremely tight pencils. Al Milgrom used to joke that all you had to do was pour ink into the corner of the page and it would flow into the grooves of the pencil. I inked issue #9 up through issue #15, which is where Starlin left Marvel for a time to go work in animation.

After I’d inked an issue of Warlock, Frank Brunner wanted to do Howard the Duck out here. So he asked me if I would be interested in inking Howard the Duck, and in those days, both of those books were bi-monthly, and they were on alternating schedules, so I could accommodate inking Warlock and Howard the Duck at the same time. For the first year or so, both of those titles were bi-monthly. So it worked out very nicely for me.

KM: I loved all those cosmic books in the 1970s! I’m glad to see Jim Starlin back in the news with Guardians of the Galaxy. Let’s move on to the book you are on now. You’ve probably told this story a million times, but how did you start on Fables? You’ve had a an amazing twelve-year run on it.

SL: Like many of these things, it was sort of a chance pairing up that worked out really well. I’d done a little bit of work at Vertigo and a little bit of work for Shelly Bond, the editor of Fables. And they had a new book and needed an inker, and she asked me if I’d ink the first story arc, and it just worked out.

We’re at 144 issues at the moment. I didn’t ink every issue, by any means. I think of myself as part of the regular team, but there are many other artists involved. In fact, that’s one of the things that I like about Fables, is that it’s not one “look,” everyone brings their own interpretation to it. Which is the nature of actual fables, everyone does their own take. There are countless variations on these stories and different people telling them. Even though, technically in the series, it’s all Bill Willingham who’s doing the writing, of course. I think I’ve probably inked at least 100 issues.

KM: What do you think about it coming to an end, finally?

SL: Well, I think it’s a good idea in that there’s all these storylines, and now we can actually wrap them up. I always like it when things can come to a conclusion.

KM: They must be planning something special for the final issue. What can you tell me about it?

SL: I’ve penciled a couple of issues of Fables, and I’m doing something for the final issue. The final issue, #150, is going to be a giant-sized issue: 150 pages. So, there’s going to be a lot of people, different artists contributing final story arcs on all the various characters, and I’m doing one of them.

KM: Which story?

SL: Blue. Boy Blue. Currently in Fables, they’ve already started doing a couple of them. The most recent issue that I’ve seen out has the last Flycatcher story. Well, it’s just a little vignette, you might say; it’s just one page.

The thing about Fables is that, in the past I would generally switch back and forth because I’m a slow penciler, but at the same time I usually have a short attention span, so if I’m inking one book for six months straight, then that’s usually enough. But Fables has actually been a lot of fun, and it changes a lot, and Mark Buckingham is a terrific penciler who likes to change up his styles and approach often. So it keeps it all very fresh, even though it’s been twelve years, it’s still fun to work on.

KM: Trina told me that now that Fables is wrapping up, you might be considering moving into a graphic novel of your own.

SL: Since I haven’t had the opportunity to actually draw anything for ages, I have a lot of ideas I’d like to do. I’ve wanted to do stuff with Polynesian mythological elements. I have a nice concept in mind that I really am looking forward to trying. The idea started with a Robert Louis Stevenson story I illustrated, set in the South Seas. I’m interested in the contrast between tourists and the local culture.

Working on Fables has given me a lot of ideas about how to approach these things. There are so many TV shows and movies that are working off the same premise. But, oddly enough, few of them are any good.

KM: Before we wrap up, tell me about your comic book Rock band.

SL: Back in the ’80s, I was in a comic book Rock n’ Roll band: Seduction of the Innocent. Max Collins on the keyboards and vocals, Bill Mumy, who was the brains of the outfit on guitar, Miguel Ferrer playing drums. They’re all fabulous musicians. I played bass. Everyone in the band was somehow connected in the comics biz. We also had John “Chris” Christensen on drums and guitar; he’d been involved with The Spirit Picture Disk for Kitchen Sink Press.

The first time I met those guys, it was one of the San Diego parties, with a band… I just ended up in the back of the room with a bunch of guys who were saying, “Oh, I play music.” Somebody said, “Oh, you can play better than that.” And we figured we should either stop saying we could play better than that, or put a band together and actually see whether or not we could play better than that. So we did. It was a bit of a challenge, because Al Collins lived in Muscatine, Iowa, and I live in San Francisco, and Bill and Miguel both live in LA.

KM: That must have really complicated things, how did you guys work that out?

SL: We had to do it all by mail, in those pre-digital days, sending cassettes of tunes we all wanted to learn. We put together a list of songs that we all knew and could probably play without rehearsing as a core group of songs. Then we got together and it actually sounded pretty decent. Bill and Miguel and Al Collins all wrote a lot of original tunes.

Bill wrote a couple of nice tunes in honor of Jack Kirby. We had learned a couple of songs, a couple of older tunes just so that it would give them something to dance to that wasn’t loud Rock n’ Roll music. We learned the Gershwin tune “Our Love is Here to Stay,” which was a challenge, but fun. One of the highlights for me was, one of the times we played, Jack and Roz got up to dance. Every year at San Diego Comic-Con during the Eisner Awards, there’s a moment of remembrance for Jack Kirby and they always show this picture of Jack and Roz dancing. You can see Seduction of the Innocent up there behind them, providing the music for it. We were very honored to do that for Jack.

KM: The Kirby/Roz photo and more photos of the band are included in Jackie Estrada’s new book Comic Book People: Photographs from the 1970s and 1980s. Thank you Steve, and good luck with Fables and your new graphic novel project.