Art & Museums draw a crowd at SDCF and Comic-Con Museum

/Kim Munson, Adam Smith, Rob Salkowitz, and Mark Schultz on the Splashing Ink on Museum Walls panel at San Diego Comics Fest, March 2019. Photo by Eunice Verstegen.

The Museum Panel

Had a great time at San Diego Comic Fest this year. Our panel Splashing Ink on Museum Walls with Rob Salkowitz (moderator), cartoonist/illustrator Mark Schultz, SDCC Museum Executive Director Adam Smith, and myself was well-attended. We had a great discussion on several topics. After a brief intro, Rob led a discussion of recent shows that combined old master fine art and comics, like Botticelli and graphic novelist Karl Stevens in Botticelli: Heroines + Heroes at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum (Boston).

We had a lengthy conversation about the issue of narrative, and different techniques used by artists and curators to display art and still pay attention to the storytelling function of comics. This was a special concern of Mark’s as his books contain complex stories. We talked about shows that display entire books, like Speigelman’s Co-Mix and Crumb’s Genesis, as well as shows that focused on shorter stories, covers, and a sequence of pages that show a story arc within a larger story.

Adam talked a bit about how the museum is developing and his excitement about having the museum’s first official opening night party for Cover Story just two nights prior to the panel (photos below). He also spoke about about the museum’s experiments with the concept of fan sourced exhibits, and about the strong grassroots support the museum is getting.

I talked a bit about history. Although we had a agreed to talk mostly about recent shows from the last five or six years, I made a quick detour into the 1930s and 40s, because people still think of comics shows as a new thing that has just appeared over the last decade. I also talked about the importance of seeing the original artwork with all the notes and marking for the viewing audience and for other artists.

In audience questions, one audience member accused us of dismissing the important MOMA show High & Low, which eventually led to Masters of American Comics, which was organized in response. The panel touched on it briefly. To me, High & Low and Masters are part of a two decade story that is hard to tell in a couple of sentences (I dedicate an entire section of my book to the dialog between these two shows).

Another audience member wondered if there had ever been a show of pop art style photographic blow-ups of comics panels. I told him that this was tried back in 1967 at the Louvre and no one has done a show exclusively of blow-ups since. Bande dessinee et figuration narrative , was organized by SOCCERLID, group of French intellectuals who loved American comics of the 30s and 40s, They used pop art style blow-ups of comics panels (Caniff, Hogarth, etc) in response to the comics based paintings of Roy Lichtenstein, whom they despised. After the show closed in Paris, it toured to several European capitals in the late 1960s. The Institute of Contemporary Art in London originally planned to have this show, but opted instead to assemble an exhibit of original art. By the mid-1970s, museums, curators, and artists decided that the blow-ups were inauthentic, were kind of insulting (a different way of turning comics into Pop Art), and missed all the elements that made comics unique, like layout and narrative. Audiences valued the aura of authenticity seen in the originals and they appreciated learning about the creative process through all the markings, white-out and other notations. Many shows use blow-ups to show detail or as a design element, but no one has ever done a show of nothing but Pop Art style blow-ups since. Even Masters of American Comics, which specifically focused on visual form, did not do this.

We were all grateful to the audience, who were intellectually engaged and curious throughout the panel.

Barbara “Willy” Mendes, Mark Bode, and Trina Robbins hold up copies of the “East Village Other” during the “Gothic Blimp Works” panel.

Other Great Panels!

All attendees I spoke with were impressed with the selection of panels scheduled, as well as a robust dealer room and artist’s alley. I particularly enjoyed Urban Geography and Comics, led by Dr. Lisa Chaddock; The Beginnings of Modern Mythology, Pop Culture and Modern Superheroes and Villains an overview by David Lemmo; The 1950s Made Kurtzman MAD with Michael Dooley and Bill Schelly; Pioneers of Comix with Mary Gleener, Lee Marrs, Willy Mendes, and Trina Robbins; Ditko: An Arlen Schumer VisuaLecture; Mary Fleener’s First Graphic Novel “Billy the Bee” (one of my favorite panels) with Fleener, Mark Habegger, and James Nieh, PhD (a bee specialist); a special remembrance of Batton Lash, a pillar of SDCC, who was lost to us earlier this year, with Anina Bennett, Jackie Estrada, Mark Evenier, Paul Guinan, Rob Salkowitz, Artlen Schumer, and Scott Shaw!; Comics, Space Travels, to the Moon & Beyond with Michael Dooley and Benjamin Dickow; and spotlights on Vaughn Bode, Willy Mendes, and Mark Schultz. I wish I could have cloned myself to get to more!

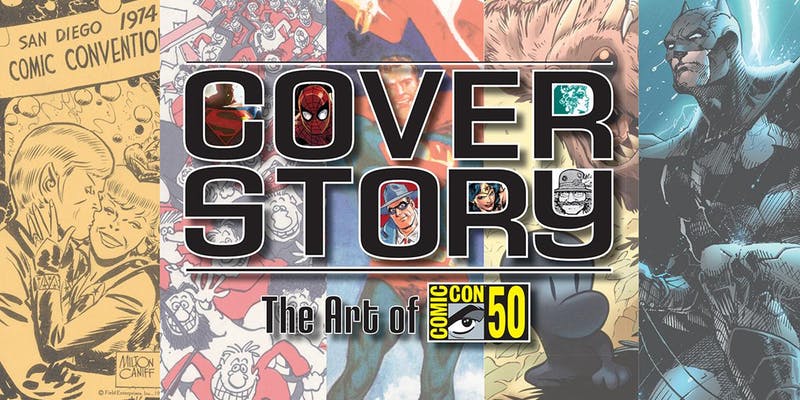

Cover Story at the San Diego Comic-Con Museum

2019 marks 50 years of SDCC, making it the longest continuously run comics and pop culture convention in North America. This show displayed sketches, paintings, and finished versions for yearly souvenir books pulled from Comic-Con’s archives and private collections. The opening night party, open to Charter Members, included an Eisner Week panel in the Museum’s theatre with Jackie Estrada, IDW’s Scott Dunbier, moderated by Charles Brownstein of CBLDF. Aside from the theatre and the gallery set up for Cover Story, the museum is a cavernous, three story space awaiting a top to bottom remodel.